In the trail of the snail song

- Merve Duran

- 22 Eki 2025

- 9 dakikada okunur

Güncelleme tarihi: 4 Kas 2025

Farah Al Qasimi’s first solo exhibition in Istanbul, Desert Hyacinth, takes place at SANATORIUM between September 12 and October 26, 2025, curated by Ulya Soley. We explore Al Qasimi’s exhibition, which makes visible the complex bond that desire forges with the capitalist order, consumer culture, gender, and ecological destruction

Words: Merve Duran

Farah Al Qasimi, Surge, Video, 8 minutes 39 seconds

“I desire the things which will destroy me in the end.”

- Sylvia Plath

Children grow up with fairy tales. These narratives often teach that desires without limits demand great sacrifices. To attain their desires, heroes must give up their freedom, their bodies, or even their lives. Fairy tales also serve to discipline desire, reinforcing norms such as gender, obedience, and ownership. In Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, the mermaid who sacrifices her voice and life for unrequited love and a pair of human legs to reach land exemplifies this duality of desire and cost. Farah Al Qasimi’s first solo exhibition in Istanbul, Desert Hyacinth, on view at SANATORIUM through October 26, 2025, curated by Ulya Soley, reads this popular fairy tale as an intersection of industrialization, consumption, speed, and desire, opening space for alternative ways of looking at desire.

As a child, I watched the 1975 anime adaptation of The Little Mermaid and remained under its spell for a long time. The mournful, traumatic cries of the mermaid Marina, who dies for love and turns into multicolored foam on the horizon, and her closest friend, the dolphin Fritz, as they accompany her spirit dissolving into the sea and sky, still linger in my mind. What reawakens these images within me is Surge, the most striking work in the exhibition, which moves fluidly between photography, video, and music.

Before encountering the video, the large-scale foil prints and photographs on the ground floor serve as a threshold into the artist’s visual language and her fantastical world. The exhibition begins with the feeling of stepping into a dreamlike atmosphere, while the video on the upper floor lifts the veil behind this seemingly colorful and playful world. At moments unsettling and ironic, the video provokes a series of questions: What are the limits of our desires, and of what we are willing to sacrifice for them? More importantly, how much longer will we remain spectators to the subjugation of those desires by capitalism and social norms?

Left: Farah Al Qasimi, Desert Hyacinth, 2025, Archival inkjet print, 76 x 53.5 cm, 5 + 2 AP Right: Farah Al Qasimi, Desert Hyacinth, 2025, Exhibition view. Courtesy of SANATORIUM and the artist

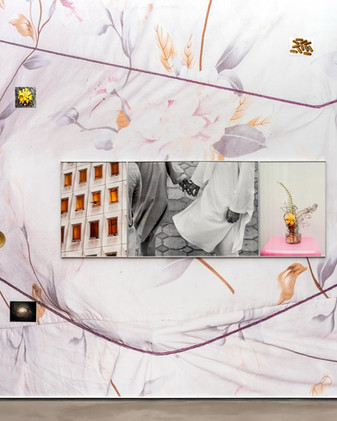

Located in SANATORIUM’s new building, Desert Hyacinth takes its title from a beautiful and resilient halophytic plant that grows along the coasts of the United Arab Emirates, where the artist spent her childhood. A photograph titled Desert Hyacinth, which ties this plant to notions of geography and resilience, is also part of the exhibition. Upon entering the space, visitors are greeted by a fairytale-like atmosphere created by pastel tones reminiscent of candy. At first glance, large-scale foil prints overlaid with photographs come into view; rather than focusing on individual images, the interplay between the foil backdrops and the illusion of depth they create produces a spatial experience. A purple sheet draped around the room and a floral bedspread evoke feelings of “home,” “safety,” and “intimacy,” while a foil depicting close-up water droplets on a horse’s hide and a large image of curtains reflected on a windowpane blur the distinction between “interior” and “exterior,” playing subtly with the viewer’s perception of space. The reflective surface of the foils simultaneously conceals and draws us toward the details in the framed photographs mounted upon them.

Farah Al Qasimi, Desert Hyacinth, 2025, Exhibition view. Courtesy of SANATORIUM and the artist

The photographs mounted on foil compose intriguing scenes of private moments drawn from both domestic and public settings, at once ordinary and suggestive, yet never explicitly revealing identity: two men grasping each other’s hands in a gesture that might signify friendship or something more; a giant snail resting on a woman’s arm; a desert hyacinth placed in a simple plastic container in the corner of a home. It is as if the artist summons images from the depths of the unconscious and brings queer desire to the surface. When Al Qasimi’s subjects are human, their faces and identities remain unseen throughout the exhibition. In one of her talks, the artist articulates this ethical stance clearly: “I don’t think anyone owes the world their entire self.”

Farah Al Qasimi, Desert Hyacinth, 2025, Exhibition view. Courtesy of SANATORIUM and the artist

Most of the interior photographs, taken in the United Arab Emirates, are saturated with color and pattern. In an interview, the artist describes the Abu Dhabi of her childhood as “a hyper-colored world.” Now living in New York, she sustains her connection to the intercultural heritage of the region where she was born through an aesthetic that might be described as cool kitsch, one that blends vivid, shiny, and kitschy elements with irony and deliberate stylistic awareness.

Among the works on the ground floor, the series Six Different Screams, in which the artist photographs the inside of her own mouth, provokes both discomfort and curiosity at first glance through its visual and structural intensity. These images of the mouth recall Francis Bacon’s persistent depictions of screaming mouths and the multiple interpretive possibilities tied to their representation. Taken during the pandemic, Al Qasimi’s photographs remind us how the mouth, opened daily to scream or to resist, has been silenced under the repressive regimes of power.

Farah Al Qasimi, Surge, Video, 8 minutes 39 seconds

Accompanied by these uncanny, silent screams, the viewer ascends thoughtfully to the upper floor and suddenly feels transported into another realm. The roughly eight-minute video Surge, composed of three parts, unfolds rapidly and evokes an urge to watch it again without leaving one’s seat. The video opens with its first section, Bone. We follow a narrator who, as a child in Ras Al Khaimah, nearly drowned and now reflects throughout the segment on their relationship with water. While searching the water for traces of childhood, they encounter the villa complexes and hotels crowding the shores and confront the reality that even flamingos have been forced to abandon these spaces. The desalination plants that extract water from the sea to produce drinking and irrigation water, only to discharge the saline waste back into the ocean, are juxtaposed with the idea of how soil, nature, and fertility are being drained through consumption. Like the desiccating quality of salt, capitalist desires and rapid consumption also dry out the world, the costs are heavy, and coral reefs and countless others are “sacrificed.”

Surge reveals how water sustains both living beings and the city, which itself operates like a living organism. Yet the damage inflicted upon the environment by the species that exploits water for human benefit, while struggling to access it is made visible through the story of fish who use water not as a resource but as a habitat. In this desiccated landscape, fish confined to aquariums cry out in human voices, “Help us!” Although this anthropomorphic choice could be criticized as anthropocentric, the artist’s aim is to trigger empathy, to make the urgency of human cruelty toward other species immediately graspable. Sadly, beings who speak with a human voice and language are often perceived as more “serious” and “familiar.” Later in the video, we see captured fish still gasping in icy buckets. Deprived of their habitats and basic needs, they are reduced to mere food commodities. Up to this point, everything unfolds rapidly, until a recurring image slows down the flow: we watch as the scales of a fish are plucked one by one by human fingers. The repetition confronts us viscerally with our own actions and the harm we cause, as though our fingernails were being pulled out or our skin peeled away. Over this sequence, an iPhone screen flashes “cute” photographs of fish, positioning us in the role of both witness and accomplice. Just then, a statement appears on the screen: “It’s not a problem to eat fish, because they don’t have feelings.” Don’t they? Of course, thinking so is the easiest way to evade responsibility, and it is precisely this ease that the work throws back at us, with biting irony.

In the second chapter, Coral, we see someone combing their hair with a fork against a patterned blue backdrop that gives the impression of being underwater. Like the first narrator, this one also recounts a near-death experience: a mermaid wounded by a fishing hook. The moment of drowning and the wound from the hook become inseparable from the relationship with water. This narrator is a direct reference to the Japanese anime adaptation of Andersen’s fairy tale that the artist watched as a child and found deeply affecting. The dancing mermaid, who trades her voice for human legs to walk on land, fails to reunite with her love and dies. The artist approaches the fairy tale as a framework for thinking about systems of production, dynamics of commodification, and the manifestation of desire; she reflects on how children’s stories construct values and perceptions of gender, focusing on the mermaid’s longing for the “prince on land.” Thus, the narrative is not merely a romantic tale, it offers a sharp reading of how global economies of desire, commodification, and gender norms are produced.

Farah Al Qasimi, Surge, Video, 8 minutes 39 seconds

Within the desire economy, the pearl emerges as both a luxury commodity derived from the exploitation of an animal and a symbol of the mermaid’s abandoned underwater life—a trace of what she has sacrificed for love. Amid the rapidly shifting imagery, an iPhone screen now shows TikTok videos where salt is poured over snails “for fun,” confronting us with the transformation of cruelty into an object of visual consumption. Al Qasimi not only constructs the narrative through filmed footage and found videos sourced from social media but also undertakes the music and voiceover herself. The soundtrack rises and falls, shifting in tempo as it aligns with the accelerating rhythm of consumption, social media, extinction, and exploitation, until, in the third chapter, it gives way to a song.

In the third chapter, Snail Song, an African giant snail, named after SpongeBob’s pet snail, Gary, and companioned by one of the artist’s close friends, appears as a blue velvet curtain opens. Gliding gently across a red-polished hand, the snail moves forward, leaving behind a luminous silvery trace. Here, the velocity of the previous two chapters subsides; slowness takes precedence, revealing a tactile, bodily encounter between two different species. This moment functions as a pause, a reflective turn toward everything that has been consumed, sacrificed, or lost.

The snail that sings in a human voice points to our tiny position within the meaninglessness of life, our helplessness, and our transience in a world we have desiccated and destroyed through capitalist, hierarchical desires. As the snail slowly moves across a hand for minutes on end, its words, “I can’t make a sound”, link both to the little mermaid who sacrificed her voice for desire and to our own limited power in the face of today’s climate crisis and the loss of ecological diversity. Violence and its consequences are not always immediate or visible. As Rob Nixon’s concept of “slow violence” suggests, environmental destruction, exploitation, and inequality often unfold over time as invisible, accumulative processes that seep into the flow of daily life, normalizing catastrophe. Their effects eventually become visible, perhaps not sudden, but vast and irreversible.

At the end of each chapter, a painting by William Turner appears. This sequence can be read as a reminder that the natural world, which initially seems enchanting and serene, also harbors a terrifying force, one we forget or choose to ignore through human arrogance. As industrialization and technological progress reinforce the illusion that life has become easier and that nature is under human control, Turner’s A Storm (Shipwreck) reveals how nature’s overwhelming power can erupt in an instant, leveling everything. This formidable reality reverberates with the fragility of the snail’s song.

When Surge is brought together with the photographs and prints on the lower floor, it establishes a cohesive world of meaning, becoming the central and most striking element of the exhibition. To conclude from where the video leaves off: when we set aside, even momentarily, our capitalist desires fueled by speed and the frenzy of consumption, and instead center repair and care, recognizing our coexistence with other beings; when we reclaim attention against the incessant stimuli of social media and the velocity of our lives, and allow ourselves to slow down, we may begin to perceive the magic of the moment and realize the futility of the desires we have been chasing.

The exhibition can also be read through two living metaphors without centering the human: the desert hyacinth, lending its name to the show, symbolizes endurance and resilience, a beauty that persists even in a “dried-out” landscape, flourishing along saline shores. The snail, on the other hand, represents not merely “slowness,” but a call to live time attentively and with trace rather than haste. For this reason, I conclude with a line from Mary Oliver’s poem Softest of Mornings, which captures the tension between attention and ambition through the smallest of moments:

“No doubt clocks are ticking loudly

all over the world.

I don’t hear them. The snail’s pale horns

extend and wave this way and that

as her fingers-body shuffles forward, leaving behind

the silvery path of her slime.

Oh, softest of mornings, how shall I break this?

How shall I move away from the snail, and the flowers?

How shall I go on, with my introspective and ambitious life?”

Farah Al Qasimi, Desert Hyacinth, 2025, Exhibition view. Courtesy of SANATORIUM and the artist

Desert Hyacinth can be visited at SANATORIUM’s new space in Emekyemez Mahallesi until October 26, 2025. For more information about the exhibition;

Yorumlar